- Home

- Jonathan Crown

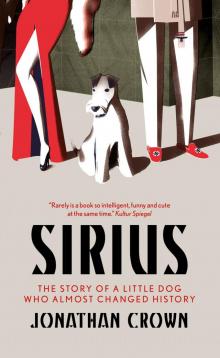

Sirius

Sirius Read online

Start Reading

About Sirius

About Jonathan Crown

Reviews

Table of Contents

www.headofzeus.com

For my family, who lived in Berlin

during that period

Part 1

EVERY MORNING, AT ten o’clock on the dot, Professor Liliencron steps out of his house, and what happens next is always the same: he draws in a deep breath of air, as if he were standing on a mountaintop in the Alps, drinking in the healthy climate. Even his clothes are suggestive of this wanderlust: a flat cap, a hiking jacket, knee breeches. Next to him, ready and waiting, is his fox terrier. The dog waves his tail expectantly, thinking “Now we’re off!” Then the two of them trot down Klamtstrasse, a small side street just off Berlin’s Kurfürstendamm. At the first tree, they stop. The dog snuffles around. Herr Liliencron pulls a book out of his jacket pocket and reads. Nothing disturbs their tranquillity. Neighbours call out their greetings. Herr Liliencron nods back in a friendly fashion, then immerses himself in his book once more. Meanwhile, the dog circles the tree, as swiftly as he can, his snout always right up next to the trunk, where a few blades of grass grow. Sometimes he barks at the tree, growling invitingly as if he wants to play with it. Then he lifts his leg.

This can continue for a good half hour. Eventually, Herr Liliencron claps his book shut, puts it away in his pocket and prepares to set off back home. The dog has no such intentions. He wants to play with the tree for longer, much longer. Herr Liliencron calls his name, softly but sternly: “Levi!”

Levi knows that he is the one being addressed. Every single time this happens, he tries to put on an expression which – in his opinion, at least – can’t fail to have a heart-wrenching impact. He accompanies this with a pitiful yelp, drooping his tail and nestling up close to the tree as a gesture of deeply felt inseparability.

Herr Liliencron begins to head off. As he walks away, he casually unwraps a bar of chocolate, as if it were mere coincidence that he should do so at this moment. The crackle of the paper wrapping weakens Levi’s resolve. The tree will still be there tomorrow, he thinks to himself. Transitory things should always take precedence.

The professor and his dog. Always at the same time, always at the same tree. In the heart of Berlin.

*

The Liliencron family live in a grand townhouse, which the Leopoldina – the German National Academy of Sciences – has put at the disposal of its honorary member.

Professor Carl Liliencron has held this role since he was awarded with the golden Cothenius Medal. Soon after, he moved into the stately residence with his wife Rahel and their two children, Georg and Else.

“This house needs a dog,” he declared ceremoniously. And that was how Levi came into their lives.

Now it is spring. In the year 1938.

In the long history of the Leopoldina, Carl Liliencron is its youngest dignitary. Forty-two years young. And yet his hair is already white, sticking up erratically from the sides of his balding pate in a manner befitting of the bearer of the Cothenius Medal. Sometimes, nature knows in advance what the world has in store for someone.

Liliencron’s subject is microscopy. At his institute, he researches the relationships between Arctic and Antarctic plankton.

“Anything bigger than four thousandth of a millimetre is of no interest to me,” he is fond of saying.

This is also how he explains his disinterest in Adolf Hitler. And politics. And the future. His opinion on these things is that they are “all too big.”

And this man, of all people, who declares everything visible to the naked eye to be inconsequential, has a wife whose beauty cannot fail to be seen at the very first glance. Isn’t that strange?

Rahel’s beauty has long been the talk of Berlin. She had famous suitors, like Wilhelm Furtwängel and Peter Lorre. But she chose the man with the microscope. “He sees the unseeable. That’s such a hoot, don’t you think?”

Rahel Liliencron takes a cheerful approach to life. First thing in the morning, while she gets dressed and does her hair, joyful music already pours out from the gramophone. Records that are all the rage in the dance halls of Berlin.

“Come on, Carl,” she says to her husband. “Dance with me!” He shakes his head. Too young for the Cothenius Medal, too old for the here and now, he thinks. It’s odd, really.

Sometimes, though, he does dance with her.

Rahel loves fashion. Her sister, who lives in Paris, sends her the latest couture magazines. Rahel then has the clothes made. And quickly! She wants to be the first in Berlin to cause a stir with the season’s newest trends.

To this day, Rahel still doesn’t know exactly what plankton are. “But the most important thing is that you know,” she says to Carl.

She shows him a pink outfit the seamstress has just finished for her. A Coco Chanel design. “I bet your plankton can’t do this.”

“That’s where you’re mistaken, my love,” answers Carl. “The green algae adapt their shading every season. According to the wavelength of the light absorbed through their membranes.” He smiles lovingly. “I’m quoting from my definitive reference work Phytoplankton and Photosynthesis. You can read up on it there.”

Rahel knows the book. It’s one of the weighty tomes she fetches from the library while Carl is in the institute during the day. She piles the books up on top of one another on the floor. “Levi,” she calls. “Time to play. Come on, up we go!”

Levi is a clever dog. After three or four attempts he knows what’s being asked of him. Sometimes he jumps over the obstacle, sometimes he enthrones himself on it and plays “sit up and beg”.

Or, at the command “Levi, read!” he acts as though he is leafing through the book with his paws. Then he slumps theatrically, closes his eyes and snores.

He loves these little performances.

In the late afternoon, Carl often comes back home with a few colleagues from the Academy. They retreat to the library, drink cognac and discuss work matters. Professor Hertz is there, the Nobel Prize Laureate for Physics, and Rafael Honigstein, the famous palaeontologist. Recently, their conversations have had a tendency to stray away from the natural sciences and towards politics instead. The Nuremberg Laws. The book burning. The harassment of Jewish academics and students. These are bleak times. What can be done?

Levi listens attentively.

Soon, the moment comes in which Liliencron paces over to the bookshelves and, with a furious flourish, holds Mein Kampf up in the air.

Levi gets to his feet, barks several times as loud as he can, then extends his right paw up high in a Hitler salute. Another trick that Rahel has taught him.

The academic gathering applauds. They also know that this is the signal: it is time for them to head home.

“You still need to teach him to do his business on that book,” says Carl to his wife, who accompanies the guests to the door.

Evenings in the Liliencron house are dedicated to the family. Putti, their Swiss maid, serves dinner in the conservatory. Later, Else gives a short concert on the piano.

“She has talent,” the conductor Fritz Mahler once said. He is a friend of the family, and on occasion used to accompany Else on the piano. “But I doubt very much that it would be to our Führer’s liking.”

Mahler emigrated to New York two years ago, and wanted to take Else with him. But her parents thought she was too young. She was thirteen at the time.

The black Beckstein piano stands in the salon. Else is playing the second movement of Schubert’s sonata in B-flat major. A melancholy andante which becomes increasingly delicate, fading more and more, until only the hint of a touch brushes the keys. All of a sudden, the mighty piano is whispering tones which are almost inaudible.

Else see

ms to be drowning in the music. Her red hair tumbles down onto the keys in waves, her pale skin is reflected in the surface of the piano as if in a deep, dark ocean. The last accord: Death and the Maiden.

At this moment, Else feels the impatience of her heart. The longing for her first great love. When will it finally come?

Georg is her older brother. He will soon be sitting his final exams at the Fichte Gymnasium. He is the last “non-Aryan” student in his year group. He wants to become a doctor, but Jewish students are prohibited from going to university.

Father Liliencron remains steadfast: “Sauerbruch promised to put in a good word for you, remember.”

By the age of six, Georg was already dissecting cats; the skulls of the little creatures, preserved in Formalin, still stand on his desk to this day.

He always wears a suit and tie to school. By the time he gets home, his clothes are often tattered. “Self-defence” is his usual comment, accompanied by a shrug of the shoulders. He smiles wickedly at the thought of the blows his attackers had to take in return.

Georg is a member of the East Berlin Sports Association. His trainer is Werner Seelenbinder, the German champion of light heavyweight wrestling, who refused to do the Hitler salute on the winner’s podium at the 1936 Olympic Games.

Refusal? Resistance? Resignation? Flight?

Georg’s thoughts are going around in circles, and the circles keep getting smaller and smaller. He knows there isn’t much time left. The future, this unpredictable monster, is marching towards the Liliencrons with its flag brandished in the air – and then what?

“Look at that sky!” calls Rahel, stepping out onto the terrace. “So starry and clear.”

The Liliencron family gathers beneath the firmament. There is a new moon. “Look, there’s Sirius,” says Father Liliencron with delight. “Do you see?”

His finger points up into the darkness, to where light is still burning at the end of the universe.

“The constellation is called Big Dog.”

Levi lifts his head. His gaze follows the finger into the black night. Big Dog. He suddenly feels sad, thinking back to the day when he was small. Very small.

*

Back when the Liliencrons were on the lookout for a suitable dog, the dachshund Kuno von Schwertberg – Kurwenal for short – was making headlines.

He belonged to Mathilde Freiin von Freytag-Loringhoven, an exponent of New Comparative Psychology in Weimar.

Kurwenal was able to read and converse. He expressed himself by barking the exact number of times to correspond with the consecutively numbered alphabet.

The famous animal psychologist William McKenzie made the journey especially from Genoa and held his business card under the dog’s nose. Kurwenal read it and then barked: “Magnzi” and “Gnoa.” He was following the phonetic alphabet, of course.

McKenzie set off on his journey home, enthralled.

Two British researchers visited Kurwenal and surprised him by asking what they were wearing on their heads. Kurwenal promptly answered: “Fancy hats.”

It wasn’t long before a delegation of the National Socialist Animal Protection Association took an interest in the brilliant dachshund, although admittedly with sinister ulterior motives. If speaking and thinking animals existed, then humans – like Jews, gypsies and Poles – could be speaking and thinking animals too. In other words, Untermenschen, sub-humans.

All of this brought a plan to Isidor Reich’s mind.

Isidor Reich was a young, up-and-coming zoologist, who no longer wanted to stand by and watch New Comparative Psychology risk ending up in the hands of the National Socialists. He came up with the idea of a “Jewish Kurwenal”. And that was how he began breeding fox terriers in Berlin’s Grunewald district.

His dogs’ pedigree wasn’t made up of pompous aristocratic titles like Kuno von Schwertberg, but Jewish forenames, in alphabetical order, accompanied by the litter number and breeding name Reich.

The first Reich consisted of five puppies, named Ariel, Benjamin, Chajm, David and Esther. Reich selected the dog that seemed the most eager to learn, Benjamin, and subjected him to obsessive schooling from that moment on.

From early in the morning until late at night, the dog sat at the typewriter and obediently typed out with his paw the letters Reich called out to him. After a year had passed, Benjamin was capable of transcribing a report dictated to him without any problems whatsoever.

Meanwhile, the second Reich had been whelped. Gidon, Hadassah, Irit and Jakob. This time, Jakob was the most gifted. He was without a doubt Benjamin’s son, and that’s why it was no great surprise – or perhaps it was, when you really think about it – that Jakob had writing in his blood. At the age of six months, he composed his first and very own poem.

cad a baf

bdd af dff

art ad

abd ad arrli

bed a ccat

The verse was published in Animal Souls, the journal of New Comparative Psychology. It was a triumph.

Then the third Reich came into the world: Levi, Mirjam, Natan, Oz and Ruth.

But that was the end already. One morning, the Gestapo broke down the door, and Isidor Reich was arrested and deported. All the dogs were shot dead.

All apart from one. Little Levi.

He made his way to safety just in the nick of time. A neighbour found the trembling bundle of fur at the furthermost end of the kitchen, where presumably he had been mistaken for a pillow.

The only survivor of the third Reich. Back then, Levi had no idea that what he had escaped was only the beginning of the hell to come.

*

Professor Liliencron never reads the newspapers. Not under normal circumstances, that is. His curiosity is predominantly piqued by living things which are 3.5 billion years old. And they are rarely mentioned in the newspapers, so as far as he was concerned it wasn’t worth reading them.

Today, though, he is reading the papers.

He sits at the breakfast table. Still in his dressing gown. His walk with Levi, at ten o’clock on the dot, has been waived today. Instead, Putti took the dog out and fetched the freshly baked rolls.

Rahel trembles as she pours the coffee. She knows her husband only reads the papers when bad forebodings make it absolutely necessary.

“News!” says Father Liliencron. “Interesting news. And I’m afraid it concerns us.”

“What is it?” asked Else.

He reads out loud: “The second decree for the implementation of the Law of 17 August 1938 regarding the alteration of surnames and forenames.”

He imitates the officious tone of a reading before a court of law.

“Paragraph 1. Jews are only permitted to bear such forenames as are listed in the guidelines set out by the Reich Minister of the Interior.”

He slams his fist down thunderously on the table.

“Anyone who deliberately disobeys this order will be sentenced to up to six months imprisonment.”

The noise wakes Levi. He was slumbering contentedly on his dog blanket under the table. Normally he is awoken gently from his dreams, perhaps by the scent of a slice of cheese being proffered to him, in order that he feel like a fully-fledged member of the breakfast gathering. But today is not a normal day.

Has he done something wrong? Is the commotion about him? He articulates his uncertainty with a low whimper.

“Does the law apply to dogs too?” asked Else. “Does Levi need to change his forename?”

‘It wouldn’t surprise me one bit!” responds Father Liliencron bitterly, putting on his gold-rimmed reading glasses. “Let’s read the small print.”

The family looks at him expectantly.

“Terrible,” he murmurs. “We need to start watching our backs.”

“Start?” asks Georg sarcastically. “I’ve been watching mine for a long time now.”

“I know,” nods Liliencron, “I know. But unfortunately we can’t pick and choose the times we live in.”

“Well, you

did,” retorts Georg. “You live in the past.”

Rahel interrupts: “Leave your father be, Georg.”

Levi clears his throat, drawing attention to himself.

Liliencron leans down towards him. “You don’t understand any of this. Or do you?”

Levi sits up and sways his head wistfully back and forth in rhythm with the hand stroking him.

“It’s too dangerous out there if you have a Jewish name,” Liliencron explains to his dog.

He lays the newspaper aside and gets up.

“That’s why, as of this moment, you will no longer be called Levi!” he declares. Levi furrows his brow.

“We’ll find a beautiful new name for you,” says Liliencron. “Then you can give the Aryans the runaround.”

He closes his eyes and thinks. Big Dog. The constellation pops into his mind. The evening on the terrace. His dog has grown pretty big by now, hasn’t he?

“Sirius!” The name suddenly bursts out of him.

He stares into the startled faces of his family.

“Sirius!” he repeats ceremoniously. “From this moment on, you will be called Sirius.”

Levi feels flattered. Big Dog. But at the same time he feels the responsibility weighing down on both himself and the star – of being a glimmer of light in the darkness. Dogs called Rusty have an easier ride of it.

“Sirius, come on!”

Liliencron grabs the lead, and together they leave the house.

The passers-by can’t believe their eyes. The professor, still in his dressing gown and at a much later hour than usual, is walking absent-mindedly along the street. And he’s calling his dog “Sirius”.

“Sirius, let’s go!”

Frau Zinke, the wife of the caretaker from the neighbouring building, who sometimes makes conversation with the professor on his morning walks, asks: “Isn’t that Levi?”

Liliencron answers: “No, that’s our Sirius.”

Sirius

Sirius